For one Canadian artist, the vibrancy of Japanese washi pulled her out of the darkness of mental illness.

Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka and Ashoona Ashoona with their collaborative art piece at the Fogo Island Arts gallery in 2023. The piece, “Uummatima tillirninga, I can feel my heart beat” (2021), consists of hand-carved and hand-printed relief prints on handmade paper. (Photo by Jeremy Harnum, Courtesy of Fogo Island Arts, 2023)

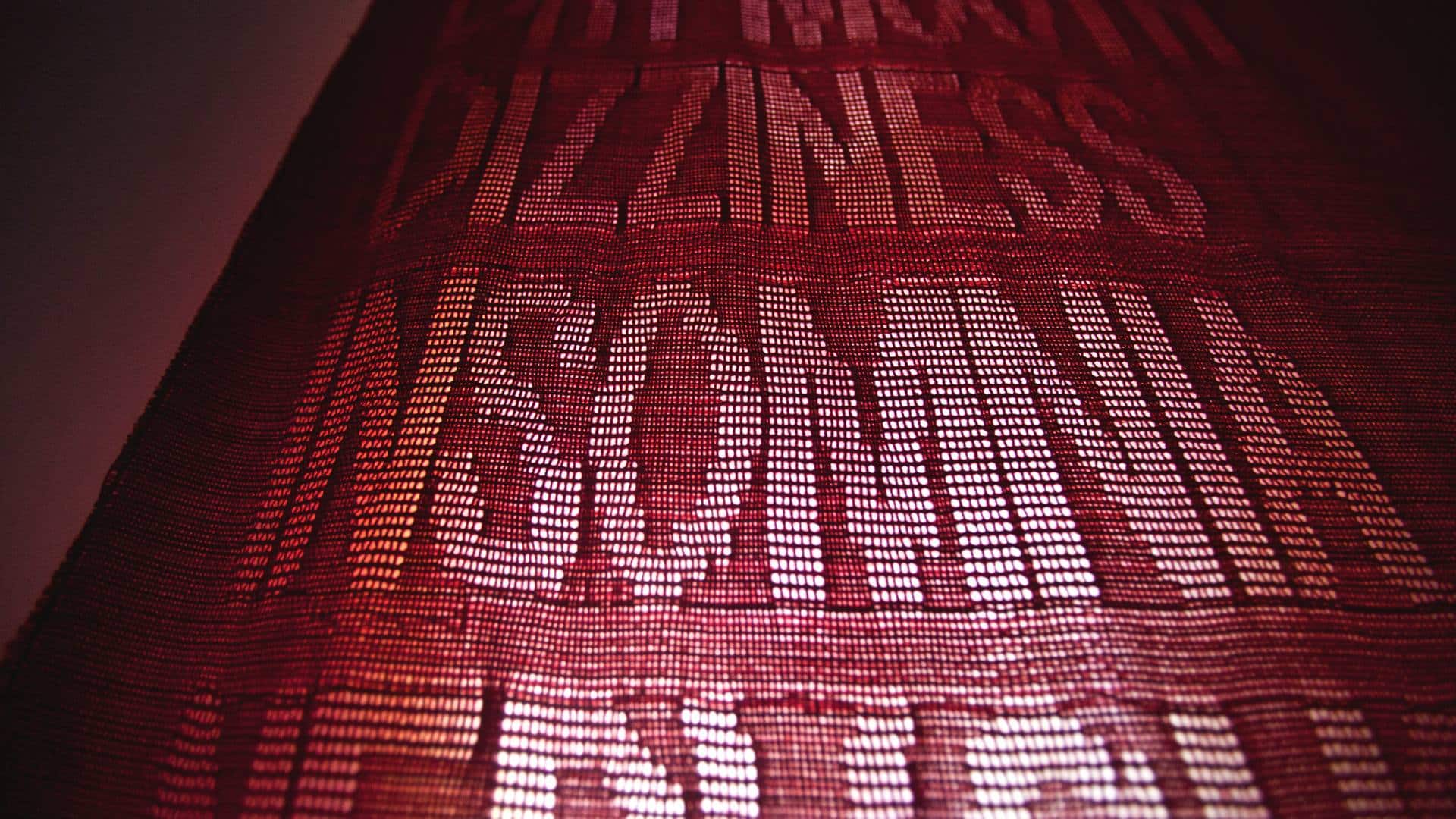

In 2014, Japanese-Canadian artist Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka began hand-weaving a list. She wove each letter into fabric with a technique typically used for lace, so they’d only be visible when placed against a light source.

The letters would eventually spell out the 75 side effects of the antidepressant medication she had stopped taking. She completed one-third of the project, titled “Take Twice Daily,” before exhaustion compelled her to set the project aside.

“I honestly don’t understand the stereotype of the brooding, melancholic artist, making their best work,” says Hatanaka. “When I’m depressed, I can’t make anything.”

Partway through the pandemic, the list began to feel relevant to her again and she returned to the project in 2021. Hatanaka finished the list and the piece was shown at the Patel Brown Art Gallery in Toronto that same year.

Hatanaka, 35, has gained international recognition for her art, particularly her pieces using washi, a thousand-year-old Japanese papermaking craft.

She is open about her mental health struggles, saying her experiences are closely tied to her ability to make works of art — in some ways beneficial, and others not.

Art as therapy

Twelve months after her exhibit at the Patel Brown Art Gallery, she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

“I was confused, self-blaming, like gaslighting myself. And over-assigning things to traumas and not buying into brain health,” she says.

She makes intricate hand-carved and hand-printed relief prints and vibrant wearable art with washi, reviving the Japanese tradition of crafting clothing from paper.

“Take Twice Daily” by Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka. Handwoven cotton, 2014-2021. (Photo courtesy of the artist)

Her work stresses the importance of ancestral knowledge and craftsmanship in fostering connection and building resilience in the face of persisting environmental and social disasters. “That kind of thing connects you with something larger than yourself,” she says.

Hatanaka finds that working with washi helps alleviate the symptoms of bipolar disorder. “There are touch points that I think would resonate with a lot of people navigating any mental health issue, particularly now,” she says.

Washi — once used for nearly everything in Japan, from building materials to clothing — is now a vanishing craft. Production of this fine paper is a lengthy and laborious process. It is made from kozo, mitsumata or gampi shrubs, which are found in remote areas of Japan and difficult to cultivate.

Farmers prune and harvest the shrubs, passing them on to craftspeople who cut and steam it into thin layers. These layers are then pressed together at family-owned paper mills where each layer is washed multiple times before being left to bleach in the sun.

Now, there is hardly any gampi left in Japan, Hatanaka says. The farmers are aging, while the children of the remaining few papermaking families are finding it difficult to keep their businesses afloat.

For Hatanaka, there is a similarity between her mental health condition and washi. The root cause of washi’s downturn cannot be isolated to just one thing, much like her bipolar disorder.

“As much as there is more normalizing of [mental illness], there is still a lot that is placed on the individual and the family, and there isn’t enough acknowledgement that these struggles are also a symptom of society,” Hatanaka says.

Hatanaka started painting in high school and studied at the Ontario College of Art and Design in 2008, where she came across washi in a printmaking class.

“Ink goes into it so deeply — it’s so luscious,” she says.

Studio featuring washi wearable art and sculptures in residence at Kashiki Seishi in Japan. (Photo by Johnny Nghiem, 2023)

Indigenous artists in an Inuit community

While researching washi, Hatanaka came across a printmaking community located in Kinngait, Nunavut, an Inuit hamlet in the Canadian Arctic that has been using washi in art for over 60 years.

“I was like ‘What is this place? I need to know more’,” she says. The discovery of a connection between a declining industry in distant Japan and an isolated community of indigenous artists in a remote part of Canada excited her.

In 2012, Hatanaka earned a degree in Fine Arts specializing in printmaking. She turned to community-engaged art across the Canadian Arctic where she worked with youth, grassroots groups and other artists. But she tended to put her solo projects aside.

Hatanaka says that she was fighting feelings of uselessness and low self-worth, which were intensified by bouts of depression. She mistakenly blamed herself for her struggles.

In 2014, she contacted Kinngait Studios at the Kenojuak Cultural Centre and Print Shop, Canada’s oldest printmaking and Inuit art studio.

The studio invited her for a three-month printmaking residency.

Connecting grandmothers a world apart

Washi is imported from Japan and purchased by the artists through a handful of distributors. The Japanese Paper Place in Toronto has been the main supplier of washi to Kinngait Studios since the early 1980s.

Two decades ago, a paper conservator at the Japanese Paper Place arranged an exchange between Inuit artists in Kinngait and the Osaka family, who owned a paper mill in Japan. Akari Kataoka had reservations about inheriting the mill due to the decline in washi use across Japan.

She travelled to Kinngait to learn more about the indigenous artists and their work with washi. The experience changed her mind about abandoning the paper mill.

Shortly thereafter, two Inuit printmakers from Kinngait travelled to Japan as part of the exchange to learn more about the craft.

Working with an Inuit printmaker, she collaborated on a large print that was exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto.

The print is a map that traces the travels of the grandmother of Ashoona Ashoona, one of the artists, across the Canadian Arctic and the Northwest Passage to Yokohama, Japan, birthplace of Hatanaka’s grandmother. The print also celebrates the connection between two distinct cultures through washi.

During the pandemic, Hatanaka’s community work was disrupted and she found herself grappling with her bipolar disorder diagnosis in isolation. Hatanaka went through her family’s personal archives and came across her grandmother’s traditional Japanese dolls made entirely from washi.

“It was this strange serendipity amid the horrors unfolding in the world,” she says. “I realized I’ve been around washi this whole time and it just didn’t register.”

In November 2022, she went to Japan for an artist residency program at Kashiki Seishi paper mill. There, she spent four months making washi and meeting craftspeople committed to preserving the craft.

While there, she spent a day making washi with Akari Kataoka.

Weaving mental health into artistic creations

Hatanaka felt focused and grounded, which prompted her commitment to raising awareness about washi and its benefits for her mental health.

Dr. Benjamin Goldstein, psychiatrist and scientific director at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, hopes that Hatanaka’s art and experiences change perceptions about bipolar disorder and reduce stigma.

“When successful individuals come forth about the fact that they have bipolar disorder, it reassures people that they are not alone and that they don’t need to curtail their ambitions because they have bipolar disorder,” he says.

Currently, Hatanaka is exploring new ways to weave mental health themes into her artwork. She is working on a piece that depicts a rise in the frequency of words like anxiety and depression in Google searches and compares that to the frequency of natural disasters.

“For a long time, I felt like I couldn’t fully express myself in the way I wanted to,” she said. “It didn’t feel possible. Now I can make art that reflects to other people their feelings or that affirms their experience or makes them feel seen.”

Three questions to consider:

- What connection did the author make between washi and her own mental health?

- How did the author connnect communities halfway across the world through her art?

- When you are sad, what things do you do to cope?

Filipa Pajevic is a freelance journalist and fellow in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.

Read more News Decoder stories about art: